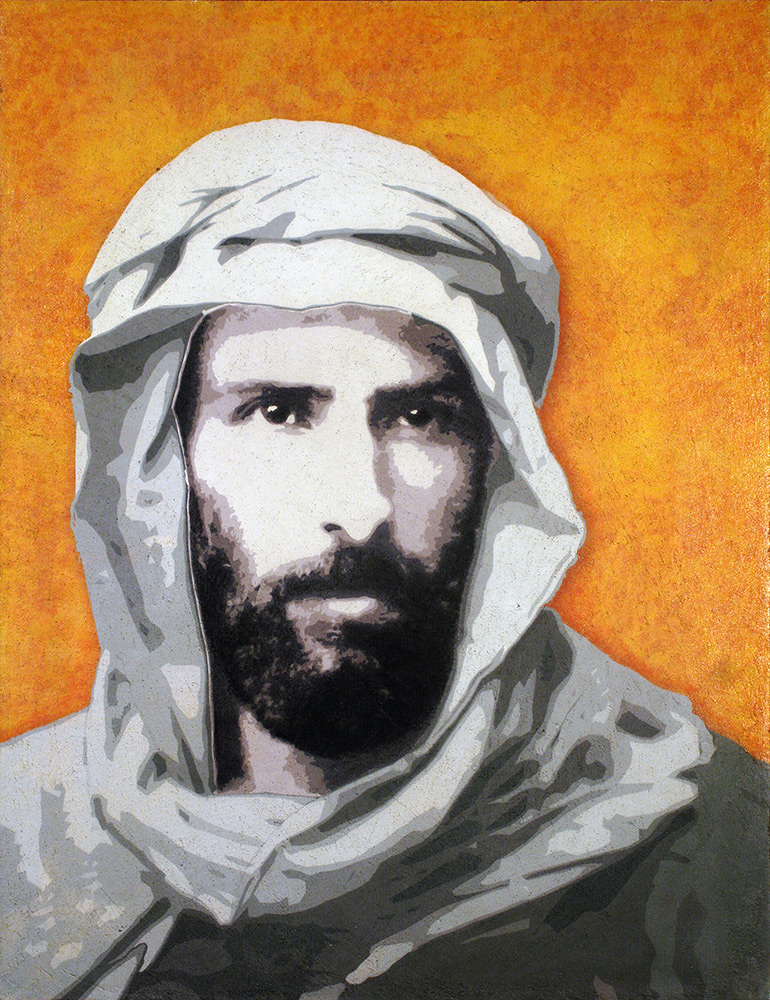

Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza

Fresco on wooden board

cm.130 x 100

(Fabrizio Ruggiero, 2014)

TRIBUTE TO TRADITIONS, A POLYPTYCH IN CONTEMPORARY ART

by Fabrizio Ruggiero

In visual art, the word “polyptych” describes a single painting with a number of elements joined together – often with hinges. In the case of Tribute to Traditions: Unity in Cultural Diversity, the 12 elements or panels form a polyptych that celebrates the concept of “one in all and all in one as undivided parts of a single whole.”

This polyptych was first exhibited in Rome, in a long hall, where it appeared as a single painting, 18 meters in length. The flexible quality of a polyptych became evident later in New York when the painting was displayed on three separate walls of a grand gallery.

In the permanent installation at the National Museum of Cameroon, this feature of the artwork is also evident because, like in New York, the painting hangs on three separate walls, but here the two last groupings of panels meet perfectly at a right angle.

This work of art was created in 2006, a date considered contemporary. However,

most art theorists maintain that the year in which an artwork is produced is not enough to classify it as “contemporary art.” The work may also not meet all the requirements necessary to classify it as “contemporary”. If it fits into a tradition, it may not be viewed as innovative, hence it is not contemporary.

The question about which are these “necessary” requirements continues to animate the discussion among art theorists, and a shared consensus has yet to be reached. Apparently, there are two schools of thought. The first school states that an object is a “work of art” if it is exhibited in a museum. The second argues that the issue is not to establish “what is art”, but rather to realize that some works transmit signs that capture our attention and communicate an extraordinary sensation which is rarely perceived through our senses, and these works may be defined as “art”. (In Greek, aesthetic means sensation, something that is perceived through senses.)

The first group of critics and curators decide what can be considered “art” and worthy to be exhibited in a museum. The second group argues that it is not correct to attribute the status of a “work of art” by simply relying on the word of these so-called recognized experts in the art world.

Some would argue that we see only patches of color in any given painting, and that the rest does not depend on the art object itself, but rather on the relationship with the viewer. The avant-garde artist, Marcel Duchamp, once wrote, “The observer makes the painting.” Certainly not all sensations emerge from an artistic source, but to talk about art ignoring aesthetics bypasses the central issue. Art is a means of communication through signs and symbols. If the role of a symbol is to act as a bridge between our daily mundane life and a more profound experience of our existence, it is obvious that the work must be placed where it can be seen and felt.

The polyptych Tribute to Traditions: Unity in Cultural Diversity has been exhibited in two prestigious centers before coming to the National Museum of Cameroon. The first time was in 2006 at the Auditorium Parco della Musica in Rome, an impressive complex designed by Renzo Piano, the most important Italian living architect. The second exhibition was in 2009 at the National Arts Club in New York, an institution dedicated to foster and promote all forms of art. Both events confirm that the painting meets the criteria set by the first school of “experts”.

This school also insists that works of art are not only physical objects, they are social objects as well. But social objects are not always “works of art”—for example, equity shares in the stock market or identity documents are social objects but not works of art.

What distinguishes an artwork from other social objects?

For the first group of critics, artworks are essentially historical visual documents with characteristics defined as “art”. For example, take the famous Monna Lisa: everyone agrees that Leonardo da Vinci did not simply take a panel of poplar wood, pour oil paints on it, and call it “Monna Lisa”. The truth is that because of Ser Francesco del Giocondo’s request, Leonardo creatively imagined his patron’s wife, Monna Lisa, as a portrait. He first made the preparatory sketches and then painted the work within the context of art commissions and the cultural codes of his age. In addition, Leonardo, always unhappy with the result, went on retouching the portrait for years, carrying it with him until his death. The first school of thought argues that all the actions that led to the execution of this painting, and all the documents related to it, must be stored and preserved in a special archive called a “museum”.

In the case of Tribute to Traditions: Unity in Cultural Diversity, the prestigious settings where it was exhibited as well as the unique circumstances that produced it, make the painting a contemporary work of art.

Although the first school of critics may have transformed art over the years to reflect and confirm their own views as experts, the second school considers aesthetics and meditates on the function of symbols and their inter-play with our knowledge, re-positioning our thoughts. Artworks then turn into “objects of experience.”

“Tribute to Traditions” precedes the subtitle “Unity in Cultural Diversity.” How should this word “traditions” be understood?

The current meaning of the word “tradition” is the transmission from one generation to the next of formal beliefs and behaviors, customs and rituals, memory and myth. Every change in the transmission affects the tradition and weakens it.

Modernity was born by questioning the beliefs of the past, (assuming that no other form of modernity exists outside the West). Change and innovation became the measure of all creativity. Even with the collapse of the revolutionary ideologies of the past century, Modernity continued unchecked.

Creativity broke with the past. In the process of denying tradition, it delved into the search for the “new” and the endlessly different. The aesthetic paradigm of avant-garde movements did not evolve through imitation of earlier styles, but in a violent break with the past. Their focus looked ahead to the future. The avant-garde movements judged art only from the “paradigm of progress,” taking art out of time, depriving it of memory.

Baudelaire wrote that modern art expresses only “… half of Art. The other half is eternal and immutable (L’autre moitié est l’eternel et l’immutable)”. According to the French poet, any true work of art is timeless and eternal, not subject to fashion. It is a dream with eyes wide open. In this sense, the polyptych, Tribute to Tradition: Unity in Cultural Diversity becomes an oxymoron because it is both contemporary and timeless.

Let's observe the polyptych from the classical point of view of traditional cultures: from ancient Greece to the Middle -Ages, from the Orient to the Renaissance where “Art” was defined as “the right way to do things”. The philosopher, Aristotle, codified this in his doctrine of the “Four Causes.”

What are these causes?

The first cause exists in the intellect of the patron where the vision takes an ideal form. In order to render it visible or tangible, the patron must turn to the artist.

In the first phase of work, the artist meditates to attain inspiration. His vision imitates the patron’s idea, trying to match the ideal form. The artist’s mental image is the “formal cause” of the original vision that he will create by working with appropriate materials. This is called “material cause”.

The artist has to use a technique to express his formal image. In this phase, he becomes a “tool driven by his art” and acts as a means to an end to create what has already been shaped by his imagination. This action is known as the “efficient cause”.

The patron’s desire for the artwork is both the first cause as well as the ultimate end,

Looking at the polyptych from the point of view of the classical tradition, one can see that all the four causes have taken place in its creation.

Let's start from the beginning: an Italian writer, Idanna Pucci, devoted to the issues of cross-cultural dialogue, decides to recount a poignant incident of respect and friendship between different cultures through the exemplary story of two historic figures, the Téké king Makoko Iloo Ier and the Italo-French explorer Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza. She chooses to tell the story of their meeting by commissioning a large painting from the Poto-Poto School of Painting in Brazzaville. The painters accept the commission with enthusiasm but, for many months, are unable to produce anything.

One night Idanna has a dream in which she sees the painting emerge like a vision. She immediately writes to the artists and describes her dream. The artists understand it and immediately go to work.

Idanna, the patron, is clearly the first cause of the artwork as well as its ultimate end. It is interesting to note how the artists remained undecided for months on how to proceed until Idanna’s dream unblocked their creative inspiration. The ideal form became fully clear through her vision. Dreams are a recurring refrain in classical iconography because dreams navigate beyond the rational and are impregnated with symbols. Dreams have a cosmic dimension and bring forth messages of destiny.

When Idanna shares her vision with the painters, her impulsive but conscious act removes their doubt and triggers them into action. When the formal cause becomes clear and defined, they pick up their brushes and paints.

Idanna with her husband Terence Ward act as patrons also to the material cause by giving the artists all the materials needed: canvas, oils, and brushes. The artists then set in motion the efficient cause, acting in unison to create the work.

The painters eloquently show us how imagination can reach beyond the confines of historical context and details. It is fascinating to observe how the artists also put aside their own individual styles in order to find a common language to express this monumental work. Looking at the videos and photos taken during the process of their work, it is exciting to watch their creativity unfold. One can tangibly see how their imagination brings to life numerous figures and symbols, using some refined techniques.

In our age, when the art world encourages individualism and artists compete for stardom, it is remarkable that the painters of Poto-Poto develop a common visual narrative that shows stylistic unity.

In his Historia Naturalis, Pliny. a Roman writer of the first century BC, suggests that painting was invented by the Egyptians six thousand years before it was introduced in Greece. He adds that its origins lay in man’s earliest history, when someone first drew a line as a boundary between light and darkness, known and unknown, order and chaos.

A black line defines the perimeter of the flat-colored spaces and envelops each like a spider's web. These black lines form a net that stretches from panel to panel, where figures and backgrounds co-exist on the same plane, giving shape to a surface where all components are equally important. The painters have ingeniously used this device to express the narration and raise it into the timeless space of myth. Although borne from history, figures follow one another, recomposing themselves chaotically and yet moving within an imaginary cosmos that has its own order.

Both Modernity and Tradition then coexist in this painting. The polyptych reflects our present epoch where dual conflicting realities are part of our lives. Daily we are all faced with “continuity” and “ruptures of time” in a perennial schizophrenic dance that asserts memory and negates it. In this context, «unity in cultural diversity” seems to offer the only possible solution for the positive coexistence of all living beings.